|

|

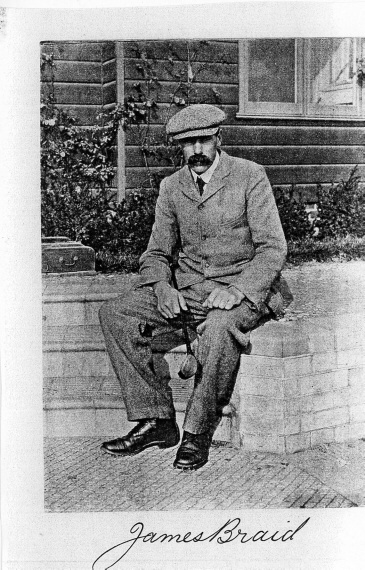

Advanced Golf

By James Braid

1908

James Braid writing on determining Par and Bogey from his book �Advanced Golf��1908

(James Braid won the British Open in 1901, 1905, 1906 and 1908. He was a famous golf course architect, and he also updated many golf courses in Scotland and the rest of the UK. Pages 250-253 are quoted directly from the book. )

I might say a word about the par and bogey calculation of such a round as that I have been speaking of. The difference between par and bogey is, of course, that the former represents perfect play and the other stands for good play, with a little margin here and there. Although it is said that "bogey never makes a mistake," it is evident that it does give a chance now and then, which par does not.

In order that the real value of the holes may be properly defined, I think that it is well to reckon that value in par figures. There is generally no doubt about the difference between 3's and 4's, but the question is as to how you shall separate the 4's and 5's. There should not be such a thing as a par 6. In a general way I would make holes of 390 yards and over, 5's. and under that distance 4's, that is when they are over 3's. The longest of the short holes must, of course, still be a 3, though it may be a bogey 4. In distinguishing the 4's and 5's, however, it is well to remember that length is not everything, and that a hole of 385 or 390 yards may be easier to get a 4 at than another hole of 360 yards. Questions of uphill and downhill, and the bunkering about the green, need to be considered, and some judgment exercised in fixing the values. I would place the par values of the holes on the course I have been writing about as follows : 4,5,4,3,4,5,3,5,5� out, 38; 4,5,3,4,5,3,5,5,5�in, 39; total, 77. A par score of this kind, however, is only for players' own knowledge and satisfaction, and is too severe for bogey competitions. One fixed and unalterable bogey score is not generally a good thing, because in certain winds quite a large proportion of the holes may have wrong values attached to them�that is to say, with the wind they may all be too easy, and against it all too difficult. It is then a simple thing and a very satisfactory one to have two bogeys for a course for the purpose of competitions, and to decide which of them shall be in force on the morning of the competition. One bogey would be set -out for one wind, and another for another. For example, if the wind was against the player at the first hole (360 yards), and with him on his return journey at the thirteenth (same length), you would make the former a bogey 5 and the latter a bogey 4, and reverse the figures if the wind were in the opposite direction. For bogey I would give 5's for every hole between 370 and 450 yards, and after that 6 might be allowed. The general bogey (with variations according to wind, as I have suggested) of the course we have been considering might be placed as follows: 5,5,5,

3,4,6,3,5,5�out, 41; 4,5,3,5,6,3,5,5,5�in, 41; total 82. It is well, for reasons already suggested, to make the bogey of the first hole easy; but there is no reason why it should be easy at the end.

However carefully the bogey score of a course is arranged, and even when two bogeys are made, it is seldom that there is complete satisfaction with the figures given to every hole. A 5 is often too much where a 4 is too little�that is to say, such a hole is an easy 5 but a difficult 4, and it will often fail to distinguish between good play and bad. What seems to be wanted is a reckoning in half strokes, and though you cannot play such halves, a stroke being a whole stroke or none at all, there does not seem to be any reason why bogey should not be considerably improved by letting him have half-strokes. To take a case, in normal conditions of wind and weather you might make the longest of those four short holes a 3-1/2, and holes of about 360 to 380 yards might be set at 4-1/2. This would mean in the former case that the man who got his 3�and it would be a good 3� would win the hole, while the man who took 4 would lose it, because almost anybody could play such a hole in 4. Even this, however, leaves a little to be desired, because at these holes it removes the chance of halves being made, when halves would often represent just the value of the play. This difficulty can be got over by allowing halves in the handicap, and seeing that they are given at the right holes. For example, at the 3-1/2 hole we have just been speaking of, we might allow the very moderate player half a stroke instead of either none at all or a full one. The result would be that if he played this hole out in 4 strokes, which would generally be the best he could do, he would halve it with bogey. This system of halves is much simpler than it may appear at the first glance, as anybody may find out after a few minutes' consideration, and it certainly seems to offer a chance of making bogey a much more satisfactory and exact sort of thing than it generally is.

|